Kranji

February 5, 2012

In May 1944, the Japanese moved the POW out of Selerang barracks to Changi gaol or to huts in its immediate vicinity. The hospital itself was divided with about a thousand patients being transferred to Kranji about ten miles away on the northern coast of Singapore island. My father was among the hospital staff who went with them. He was to remain there for the rest of the war.

My father never mentioned to me that he had been held anywhere other than Changi until a year or two before he died. Even then it only came up by chance. I had asked him how he had managed to keep his notes hidden for so long. “Oh that was easy enough,” he chuckled. “The awkward bit was when they told us to move and I had to dig them all up again!”

Move?

But then he had also only just shown me his Changi bird notes for the first time, or at least his article about them in the Bulletin of the Raffles Museum. I had known about the notes since childhood but they were never talked about. It had not even crossed my mind that they still existed. As for the Kranji notes, I would not discover them until after he died.

They do not make easy reading. In part this is because they are fragile and his writing both small and faint. Paper was very scarce and he wrote on every scrap he could find. The other reason is that for the first time he wrote about his own condition and state of mind. Both were pretty grim. Changi may not have been a holiday camp exactly, especially during the last year of the war, but it may have seemed as such from the perspective of Kranji. There were times when he wondered whether he would survive.

Not much is known about Kranji it seems. At least, not much has been published about it and I have yet to research primary sources. It is now the site of the Kranji War Memorial honouring those who died defending Singapore and Malaya during World War II.

In the following posts I will try to piece together what I can of the camp along with my father’s experience during his final year of captivity.

Nesting habits of Singapore birds

February 20, 2011

On returning home from Singapore my father focused his attention on finding a job, getting married and writing up his Changi bird notes, though not necessarily in that order. I cannot say to what extent and on what level the notes continued to be a refuge for him but he certainly devoted a considerable time to them. Within eighteen months he had completed a 112 page manuscript which included, as can be seen from the extract on the left, a detailed section on camp vegetation

the notes continued to be a refuge for him but he certainly devoted a considerable time to them. Within eighteen months he had completed a 112 page manuscript which included, as can be seen from the extract on the left, a detailed section on camp vegetation

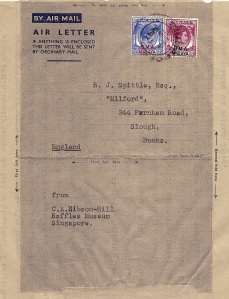

He sent the manuscript to Frederick Chasen in June, 1947. Chasen had written the definitive study of Singapore birds and had been curator of the Raffles Museum. But in July he received a reply from C.A. Gibson-Hill, who was to be the last British director of the museum, with the news that Chasen had been killed just before the fall of Singapore. A fairly lengthy correspondence then ensued with Gibson-Hill concerning the publication of the manuscript which eventually appeared in much shortened form in the Raffles Bulletin in January 1950. Both the delay and the aggressive editing were in part due to paper shortages brought about by the ‘Malaya Emergency’ (or the ‘Anti British National Liberation War’ depending on your point of view).

And that, for all my father knew, was that. About a year or so ago, however, I noticed that his article — Nesting habits of some Singapore birds –– was still available as a pdf on the web site of the Raffles Museum of Biodiversity Research, now part of the National University of Singapore. Given that I had the original carbon copies of the manuscript I thought it just possible that someone there might like to see one of them. Still, I was not prepared for the enthusiastic reply. Not only is the article still read; it apparently also remains one of the few in-depth studies of Singapore birds. There was therefore genuine interest in seeing the original manuscript, which was no longer in the museum’s records, as well as copies of the field notes (if you could call them such).

We spent a delightful day with the current ornithologist at the museum who somehow made time for us having only a few days between trips to the Sarawak interior and Christmas Island. We visited the Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve (just down the road from the Kranji camp would have been), enjoyed a leisurely meal and talked about the bird notes, Gibson-Hill and Singapore. I passed on the copy of the original manuscript that I had brought with me.

Clearly, the journey had just taken another turn.

Understatement

October 31, 2010

The original manuscript of my father’s piece on Changi Birds in the Bulletin of the Raffles Museum was considerably longer than the eventual article. One of the segments that never made it to publication was a description of the camp along with a detailed account of its vegetation.

As I have mentioned several times, my father rarely wrote directly about conditions or activities at Changi. At times – many times, in fact – you would never know that he was describing a POW camp. Perhaps he was simply being careful though it’s equally possible that this was simply the way he saw things.

Either way, his summary of the project must surely be one of the more prosaic descriptions of life at Changi.

“A project of this kind, undertaken under adverse circumstances was, however, not unnaturally beset with difficulties rarely experienced in normal times. In this respect, the continually changing conditions that prevailed in the Camp are referred to in the text: these included the large and fluctuating human population, the repeated reductions made in the size of the area, and the exploitation that was necessary to make it as self-supporting as possible. But in addition, mention may be made of the small amount of leisure-time and the rigid regulations that were imposed on the movements of personnel, the impossibility of being able adequately to compare the local bird life with that which occurred outside of the camp boundary, and the ever present uncertainty as to how long the study could be continued.”

Well, that would be one way of putting it, I suppose.

Singapore Birds

September 18, 2010

My father started making notes on the birds at Changi in November 1942 shortly after entering Roberts Hospital for pellagra and tinea cruris. This became the focus of his note taking activity for the next eighteen months until about May, 1944 and indeed turned into a research project that would not be completed until 1950 when his article ‘Nesting Habits of Some Singapore Birds’ was published in the Bulletin of the Raffles Museum.

My mother was convinced, no doubt rightly, that it was these “bird notes” above all else that kept my father going through the long years of captivity. But they were more than a simple exercise of mental discipline, it seems to me. And there was a collective aspect for he was aided by a small cadre of fellow birdwatchers. The most notable of these was E.K Allin, a former planter in Perak, who would also publish some of his observations in the Raffles Bulletin.

These “bird notes” will be the focus of my next few posts.

Ronald John “Jack” Spittle

May 2, 2009

Jack Spittle

According to his birth certificate my father was born on March 30, 1914 in Ascot though he dismissed the location as an administrative fiction. In fact, he maintained stoutly, he had been born just down the road in the village of Eton Wick. Why the distinction was so important to him I never thought to ask but it may have to do with the fact that Ascot was in Berkshire and Eton Wick, in those days at least, was just across the county boundary in Buckinghamshire. My father was a Buckinghamshire lad through and through.

As a teenager he developed a strong interest in natural history embarking on a project that was to occupy (not to say preoccupy) him until well into his eighties; a census of herons nesting at Oaken Grove, a small wood near the Thames between Henley and Marlow. After leaving school he went to work at the Farnham House Laboratory of the Imperial Institute of Entomology at Farnham Royal near Slough. Though only a lab assistant he worked closely with some of the leading entomologists of the day and illustrated a number of the Institute’s publications. He was probably at his happiest working (and learning) at Farnham House but the job did not pay well and in 1938 he qualified as a sanitary inspector and quickly got a position working for Slough Council.

He was called up in 1940 and initially joined the Oxford and Bucks Light Infantry. This wasn’t what he had in mind at all, however, and he was eventually transferred to the RAMC. Trained for anti-malarial work, he was sent to Singapore in November 1941 and after a chaotic first few weeks posted to Palau Tekong island in the Jahore Straits as sanitary assistant. It was from here that he got a “grandstand view” of the invasion of Singapore. He was a prisoner first at Changi (where he worked at Roberts Hospital) and then at Krangi, for the remainder of the war.

Returning to England he settled again in Slough marrying my mother, Jean, in 1947. He had been reappointed as sanitary inspector but within three or four years became deputy river pollution prevention officer for the Severn River Authority, another position that allowed him to pursue his entomological interests. In 1950 he published an article on the ‘Nesting Habits of Singapore Birds’ in the Bulletin of the Raffles Museum, based on his observations and hundreds of pages of notes while at Changi and Krangi. In 1961 he was appointed to a more senior position at the Devon River Authority where he remained for the rest of his career.

After retirement he got down to serious work. This involved the completion of a thirty or so year study of insect life in Devon streams, now housed at Plymouth Museum, and the writing up of his Oaken Grove project which by this time had mushroomed from a heron census to a full-blown ecological study of the wood. He was still making the three or four hour drive from Devon to Oaken Grove into his eighties; except for the war years he had visited the heronry at least annually since 1928.

While he rarely talked about his experience as a prisoner of war, he finally started to sketch out some notes about it a year or two before he died. Clearly, he was planning to write up his memories and reflections in some way and had come up with a working title: Changi Years Recollections: An Education in Frugal Living. He died in 2004.